Download (120KB). Inspired by Ronin and Sketch-n-Sketch.

Download (120KB). Inspired by Ronin and Sketch-n-Sketch.

Keeping scrollbars easy to acquire even in large files.

Thanks Artyom Bologov and Mary, though I ended up taking their suggestion in a different direction…

|

|

|

|

|

|

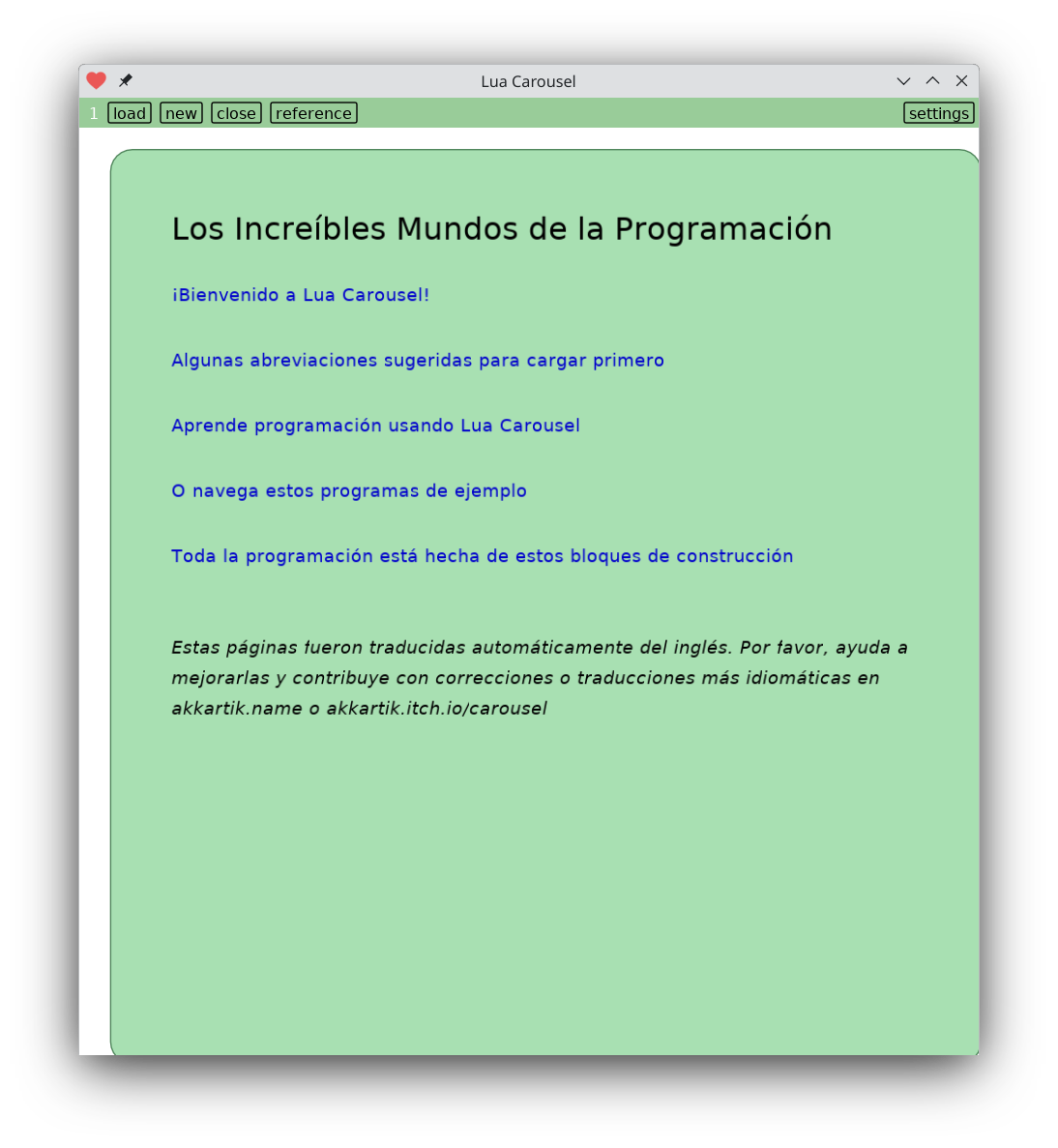

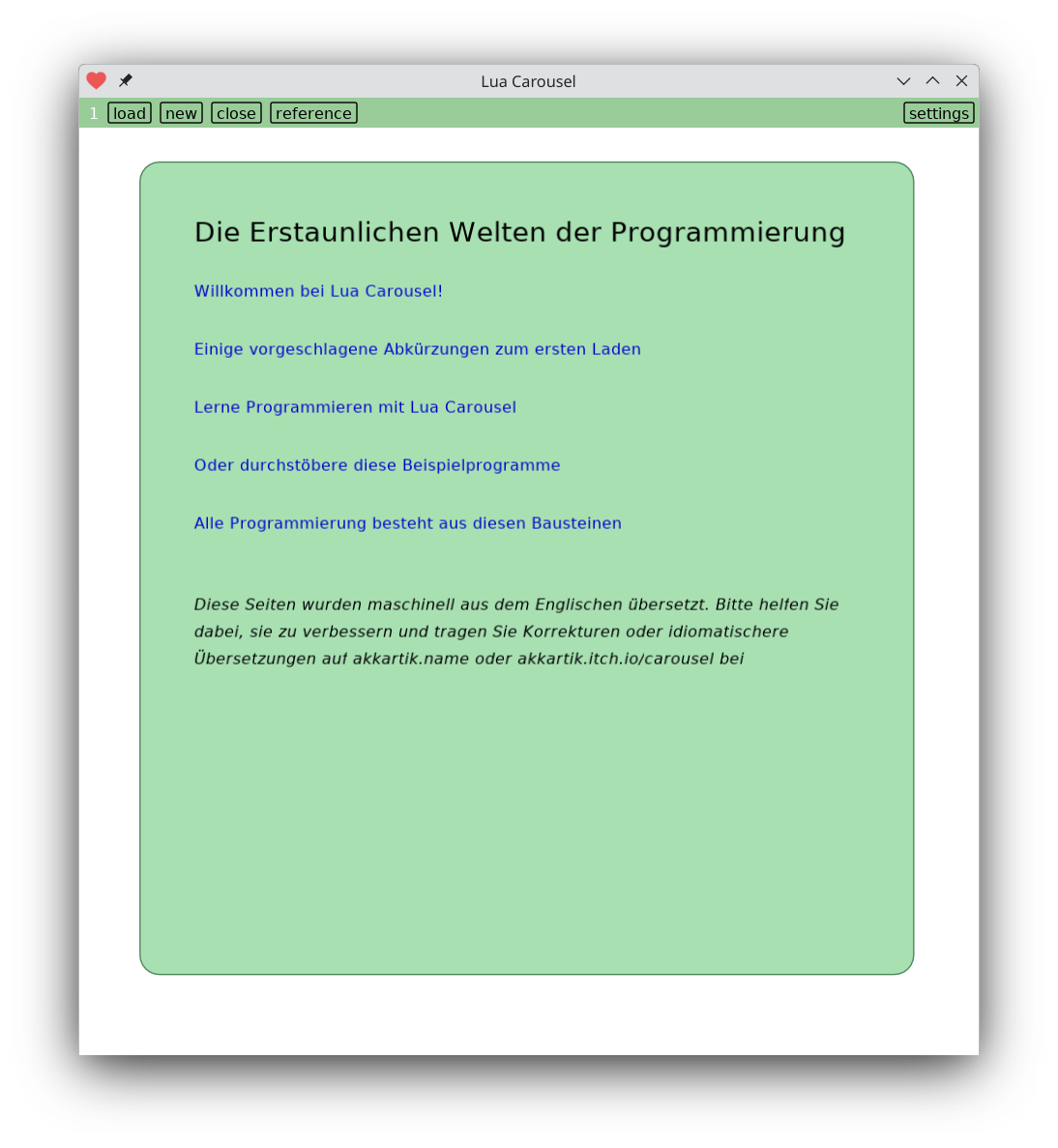

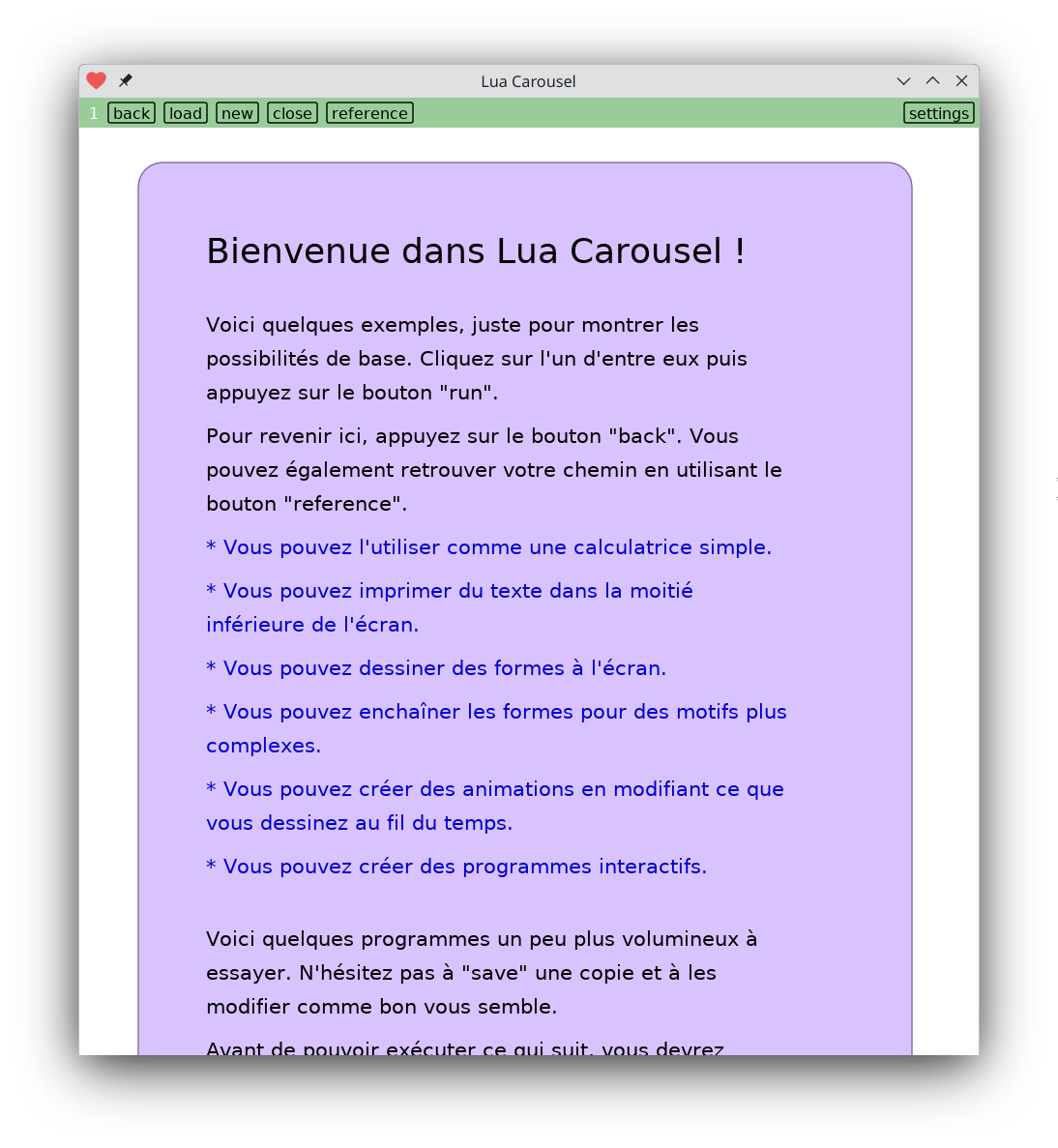

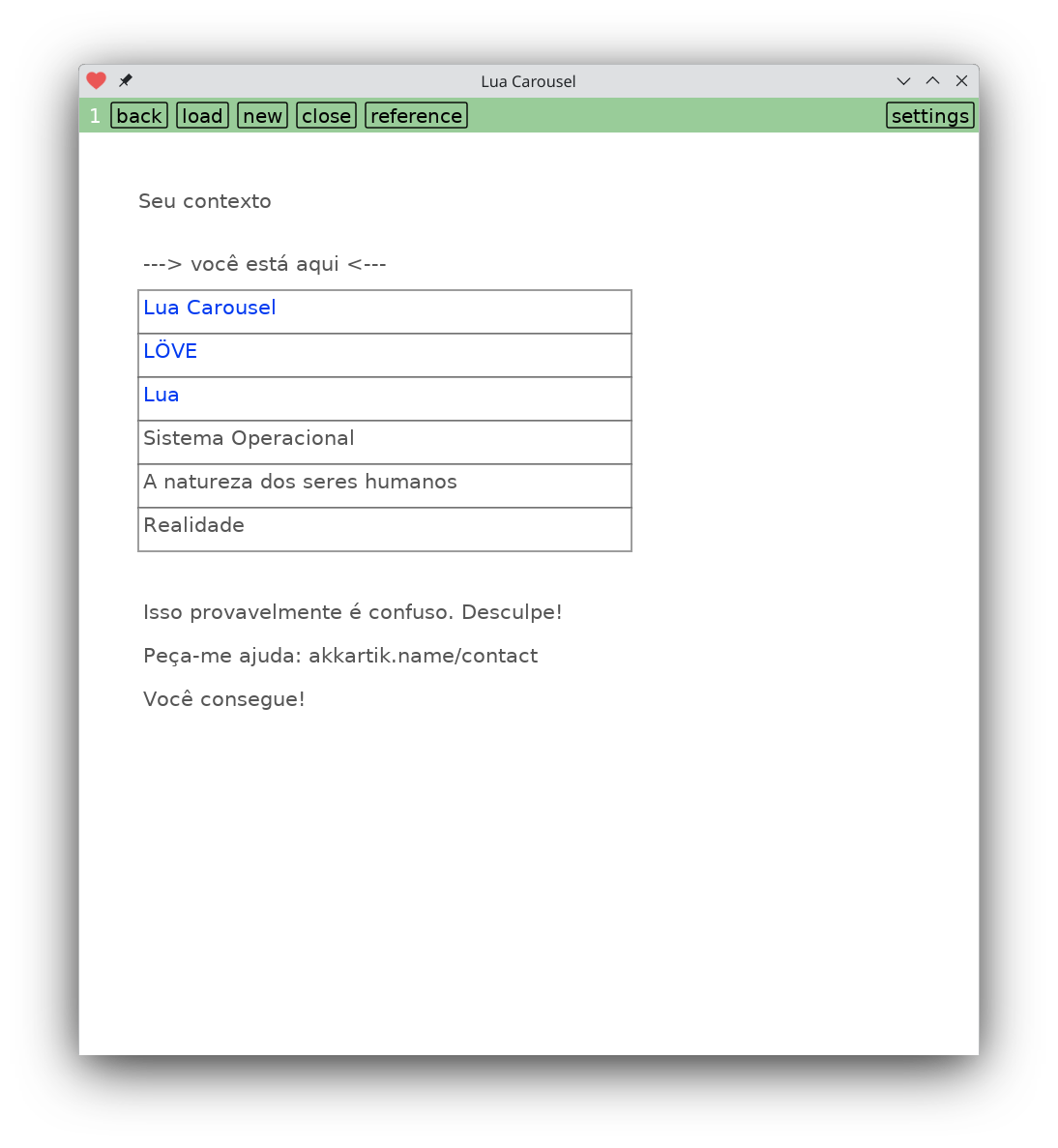

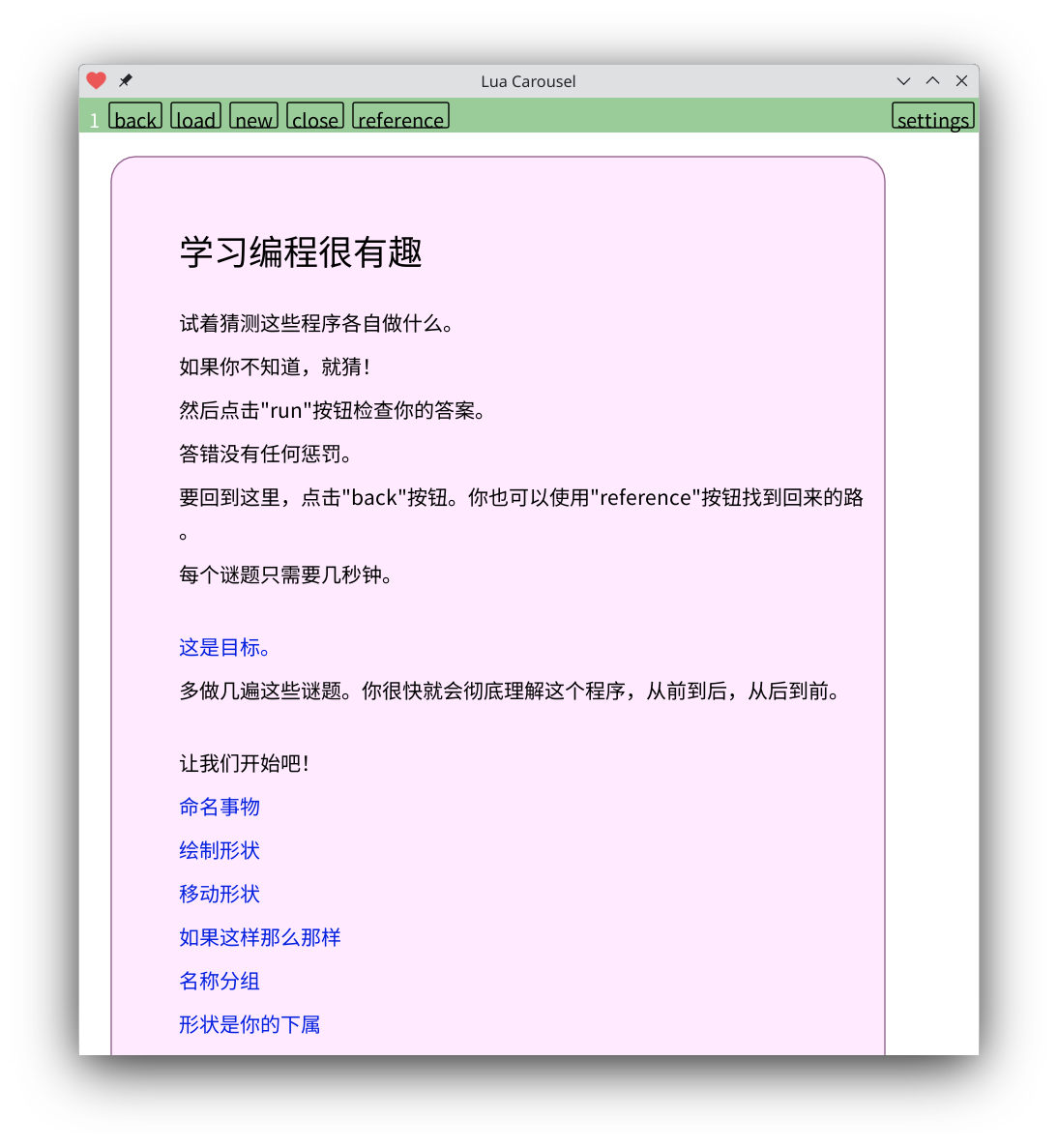

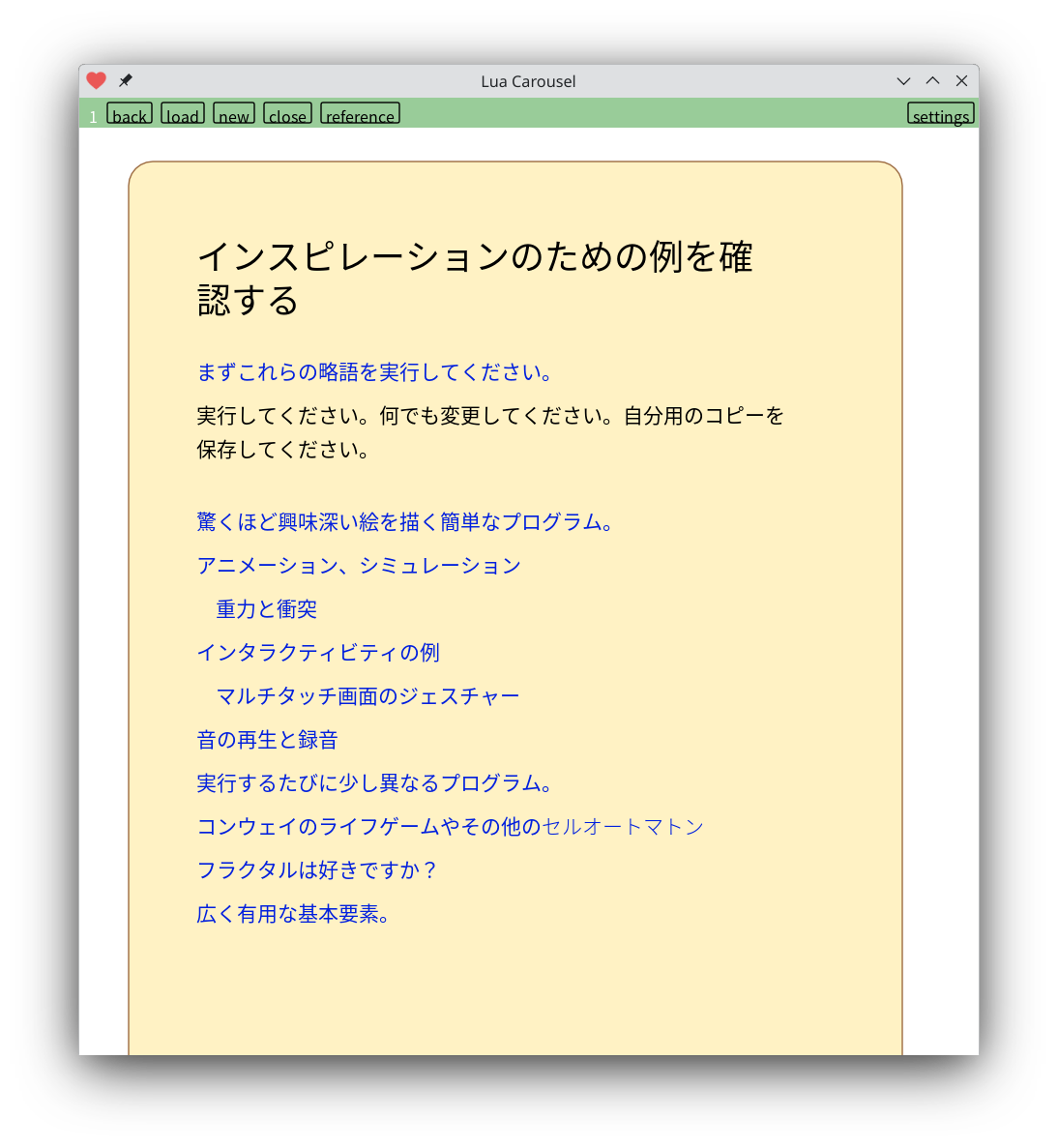

Hopefully it is helpful for someone to no longer have to put up with English.

I put each language in a separate download to reduce the amount of data you need to download.

Other languages are machine-translated from the English version. I've had friends spot-check it for obvious issues, but there are likely to be problems I missed. Please report any issues you spot. If you want to manually translate pages to improve wording and tone for your culture, contributions would be most welcome.

No support yet for right-to-left languages, or languages with combining characters. Lua Carousel still assumes every character on screen is atomic. For example, I can support Chinese and Japanese but not Korean, Arabic or Indian languages.

I don't know what I'm doing when it comes to multilingual keyboard support. My rough sense is that that's something to configure for your device. But if there's something I can change in Lua Carousel to make your life easier, please let me know.

I've included different fonts for Chinese and Japanese, which blow up the download size for these languages. The source code inside each zip file download is exactly the same, only the font files are different. The larger font files also seem to take up to 10 seconds to load.

I'm very dissatisfied with the current state of the world in two regards:

𝐀. Computer owners can't easily understand or modify programs they run.

𝐁. Computer vendors compete to limit permissions for modifying programs.

Both 𝐀 and 𝐁 have happened through the efforts of often idealistic people, but they've brought us to a world that it seems clear is going in the wrong direction:

These pragmatic solutions in turn led to more idealistic attempts to solve 𝐀 and 𝐁.

First 𝐁: Various movements (open source, right to repair) and specific actions (forking browsers, forking app stores) have tried to limit the power of vendors, but they have only ever succeeded by creating new vendors. These methods don't point towards a synthesis.

One idealistic way to get 𝐀 has been a movement toward making better use of run-time experience during the process of understanding a program. Let's call it 𝐀1.

One idealistic way to get 𝐀 has been to "render unto vendors that which belongs to vendors" and focus on domains that lead to a certain desirable social organization. Perfect freedom to make changes within a perfectly egalitarian group. Let's call it 𝐀2.

(Confusingly, 𝐀1 and 𝐀2 have both been called "live" at different times. I now tend to think of 𝐀2 as "jamming". But that's just me; I'm a nobody who hasn't integrated very far with either side.)

Moving along, a third idealistic way 𝐀3 to get 𝐀 has been attempts to move the representation of programs closer to the problem domain, to more easily convey the essence of a solution. This way tends to be called "visual", which also feels like a misnomer.

None of these has tried IMO to integrate 𝐀/𝐁, to think about the vendor/owner divide at all. However, one school 𝐀𝐁1 has and remains close to my heart: "malleable". The vision here is programs distributed by vendors who share an ethos to support owners. Lots of technical problems to be solved, but the essence of "malleable" for me is the sociopolitical ethos or stance to enable customization that is a prerequisite to doing anything here.

In the end, none of these goes far enough for my taste. I find myself in the camp 𝐀𝐁2 of "code literacy". There's a tight analogy here with prose literacy: anyone can read a novel, anyone can write an email, anyone can write a short critique on a novel, but only a few "vendors" can write novels. These goals are often aspirational in practice, but we have made huge strides in their direction over a thousand years. I want above all to bring code literacy to a similar point to prose literacy: anyone can drill down to understand a large program as it affects them, anyone can write short programs for themselves, anyone can modify large programs in small ways for themselves.

It seems really important for all camps of idealistic people to engage with the hard constraint Russell Power reminded me of, the initial post Ⅳ that led me to write this. Ever since Alan Turing and George Pólya we have known that it is impossible to systematize problem solving. Today we have close to all factual (and also non-factual) knowledge at our fingertips, but we are not close to (and I believe we will never come close to) the ability to solve all problems at our fingertips. The universe of problems has infinite variety at infinite levels of detail. All we can do is share solutions to small zones of problems that pioneers before us paid dearly for with the coin of time, and to make any of them easier to import into our brains when a situation requires. And even this we can accomplish only if we are all open to changing ourselves, to learning, to growing in some essential way closer to those pioneers.

This worldview may seem elitist, and I would very much like it to be. However, I think we are all illiterate by this standard. We live in a pre-literate society where even we programmers can only easily read short programs we wrote ourselves. Not too long ago.

[Ⅰ] Steve Krouse, "The role of the human brain in programming"

[Ⅱ] A recent thread on the Malleable Systems forum

[Ⅲ] The LIVE Primer (still under construction)

[Ⅳ] Russell Power, "Reflections on Sudoku, Or the impossibility of systematizing thought", via Bill Mill

(This post is a spiritual follow-up to this post from 2021 and this asynchronous workshop of sorts that I facilitated at FoC in 2024.)

The whole program is arranged on a 2D surface within a series of nested boxes. You can hit ‘run’, and it extracts the code from the surface and runs it and you get to play a game of Snake. (Only on a computer; even though the app runs on a phone, you can't play this particular game of Snake without arrow keys.) So it can be viewed as a sort of Literate Program, even though the representation I'm tangling from has a richer UI than is typical, a surface you can pan and zoom around with a mouse wheel or touchscreen. (It doesn't support editing yet. This is a purely reading experience for now.)

I wasn't trying to build yet another Literate Programming experience, though. What was on my mind was Christopher Alexander.

Christopher Alexander (CA) was an architect, and he indirectly inspired Design Patterns in the software world. His magnum opus was The Nature of Order, (NoO) a book I'm not sure I'll ever finish. Not because it's long (it's true that it's 4 volumes, but it has a lot of pictures) but because I often need to put it down to think about the chapter I just read for a day. And then the day turns into a week or a month or a year.

The first thing to know about The Nature of Order is it defeats attempts at summarization. With that out of the way, here's a summary of the fragments I've read:

I'm not sure I buy it to the hilt, but it feels actionable even so. I don't need to believe in the objective reality of the vector field of centers to consider the possibility that it might point us in the direction of better quality as perceived by a lot of people.

The image above is a very preliminary step at creating a more wholesome arrangement of the source code for the game of Snake, though CA would likely find it sophomoric.

I'm trying to use some well-known ideas in software design. There's a top-down decomposition here. The game of Snake consists of two screens, one where you play the game and one when the player dies.

The screen for the game itself (where the player spends the bulk of time) decomposes into 3 concepts: space, snake and food.

At this point, however, things get muddy from a classic CS perspective. These concepts are not completely separate. There are places in the program where they coil into each other. For example, I can't entirely explain how a snake grows without reference to food, and I can't explain food without reference to its purpose: growing the snake.

In response, I'm duplicating this code in multiple places on the surface, with slightly different emphasis:

To me this evokes CA's property of interlock/ambiguity. The centers of space, snake and food don't have clear boundaries here, the boundary is ambiguous and the centers kinda intertwine.

Another case of interlock/ambiguity: the screens for game and game over that I mentioned earlier are not completely separate. When the game ends, there's a great human need for some sort of conclusion to be derived from it, often in the form of a score. Did I do well or poorly? Set a personal best? Defeat my friend's score? Here the score takes into account the number of times the snake turned. You can imagine alternatives, but no matter how you calculate the score, it must make reference to the game that was just played. The two screens must share data. Here I am experimenting with indicating this permeable boundary by creating a gap in multiple levels of centers, close to uses of Nsteps, to show that the centers aren't crisply isolated from their surroundings.

I spent some time on other touches. Rather than arrange code in a vertical rectangle as we usually do, I chose to break it up horizontally to make the boundaries between definitions more easily apparent.

Viewed charitably, this might be seen as an example of what CA calls "alternating repetition", an attempt at a rhythm that resonates with the reader. Interspersing prose with code is another repetition, as are the columns. However, I tried to not make the columns or interspersed prose too monotonously regular. I tried to keep it "rough", and to hand-craft the spacing at each point rather than try to enforce some global policies for spacing and positioning.

Beware, you may get sucked into the full 4-volume opus.

Try it out. You'll need to first install LÖVE for your platform. It's tiny, completely open source, and live editable on a computer.

Here's a test build of my hypertext browser where every "page load" picks a random background. The foreground and link colors adapt to preserve a minimum contrast (WCAG AAA level).

Colors in my markup language are no longer rgb. Background colors are strings of the form 'hue:intensity:lightness', e.g. 'red:5:4' (following the perceptually uniform Oklch space). Foreground colors can contain just 'hue' or 'hue:intensity'. Missing fields get filled in to maintain contrast.

Intensity and lightness can take 8 levels (0 to 7). Hue can take one of 8 values: red, orange, yellow, green, cyan, blue, purple, magenta. Hue can also be grey, in which case it can't have an intensity. Just 'grey:lightness'.

Now, like all the best chess variants, this one uses all the rules of chess, just with one crucial, minimal tweak. So to implement Monster chess I had to first implement chess. Which I did (and not for the first time). But by the time I'd implemented all the legal moves, castling, en passant, pawn promotion, forbidden moving into check -- I was at 500+ lines of code. At that scale of program, Carousel's janky scrollbars get too thin for my fat fingers to acquire on the phone. Carousel's only nice up to 100-150 lines.

So I switched to my template repository for standalone apps using the Carousel UI. I've done this before, most notably with my Sokoban client which you can edit the source code for right on your phone. Indeed, editing the source code is the expected way to skip 10 or 60 levels. On some level everything I do stems from the desire to believe that editing source code can be a nice user experience.

I soon had a second chessboard app. But it felt like spaghetti. The Carousel template lets me split up a large program into multiple files, but with all the problems of text-based program navigation, and all my bespoke janky tools to boot. You're looking for a specific function. Which file is it in? It's hard to read code you didn't write, and on some level everything I do is an attempt to make it easier. You know, literacy. Computational literacy. The ability to read a novel of code or write an email of code. But we're not at the promised land yet, and meanwhile I have spaghetti nobody should bother with.

So I ripped out all my Carousel stuff and made it just a plain LÖVE app. File size dropped from 128KB to 8KB. So clean! But now it's not easy to modify, particularly on a phone. You have to unpack the zip file, find a text editor, etc. And on some level everything I do is an attempt to keep things easy to modify.

So I spun my wheels for a while. Eventually I remembered that I'm drawing on a graphical canvas, and that I know how to draw box-and-arrow diagrams. What I really need here, I decided, is a way to draw little box-and-arrow diagrams about my program, tapping on boxes to jump to files. It's still extremely janky, but… well, take a look.

When you run the app you're faced with a screen to select a time control. Edit it to taste, tap ‘submit’ and now you're on the main screen.

That's all there is to using the app. But there's also a button on the bottom left for editing its source code. Tapping on that brings you to this screen.

The chessboard app consists of two screens. You start out setting the timer, then you play. There's no way to go back to set the timer. You have to quit and restart the app. Timer page and main game page share two variables: start_time and increment.

Tapping on the timer page brings you to a screen of code that implements it.

|

|

I don't have any ideas to make it easier, so at this point you're stuck reading banal textual code. Hopefully the introductory screen helps find your bearings.

Tapping on the right hand box brings up a second picture, showing some substructure.

|

|

Now there are more boxes to tap on, and each of them brings you to a chunk of code to read and digest.

|

|

|

|

Again, hopefully drawing the eye to certain highlights helps get the reader oriented in a new codebase.

The drawings are just documentation so far. They're redundant with the code, and can go out of date. So I've tried to highlight only the highest level, most permanent features.

Here's another drawing about a problem I often think about: how to explain a Lisp interpreter to someone seeing it for the first time.

Arrows indicate function calls. A Lisp interpreter is a recursive function. But it can get long and complex, so it's often split into multiple functions. But now the recursion is less obvious, and it can seem intimidating to a newcomer. The word env often shows up everywhere. But as this diagram makes clear, the purpose of env is highly localized. It's only used to look up the value of a variable/symbol. Everywhere else just passes it around to get it where it's needed.

Anyways. This “markup language” (I'm just using Lua literals) for box-and-arrow diagrams and hyperlinks seems like an expressive mechanism for communicating a variety of relationships.

There's 3 tools that you can use independently:

All 3 tools use a common data source of a) files with some `---` metadata up top and a small number of VARIABLES that get substituted in, and b) index files containing a list of files that constitute a site.

All 3 tools are single-file and so self-contained and easy to move wherever you want, mix and match. For example, my site has two distinct blogs (main site and devlog). I run the first tool once and the others twice each.

I can't quite cut my site over to this, though. Open questions I ran into with my site:

<title> tag, but show no title in the <body> (because I already show the date and it would be redundant). It's unclear how to do that without a whole templating language.

I'm sure there are others. SSGs seem to be one of those things that everyone a unique-snowflake version of. But check it out if you're willing to leave Markdown behind. Using HTML is more accessible than Markdown. For example, it lets you distinguish a couple of key categories of <code>: keyboard shortcuts with <kbd>, references to names in other snippets with <var> and computer output with <samp>. Markdown's backticks can't do that. It doesn't matter if you never share your posts, and it's natural to not want to look at HTML given how monstrous it can get. But HTML also has a lovely core that a lot of civilizational effort went into, and it's sad that layers above don't use all of it. A little more manual labor can provide a nicer reading experience for others.

Thanks Cristóbal Sciutto, m15o, Eli Mellen, Tom Larkworthy and others in the Future of Coding community for inspiration.