I.get_rect which gets called on every frame and for every input event.

Here's a very silly example of the sort of app that is now easier to create:

Repo

Compare with text2.love

I.get_rect which gets called on every frame and for every input event.

Here's a very silly example of the sort of app that is now easier to create:

Repo

Compare with text2.love

Here's a longer blog post by Max.

I only had to put this rule in in one place, and all my support for editing, moving and clicking on the screen to position the cursor continues to work.

(I did need to generalize a couple of things to get to this point.)

I've been obsessed recently with the work of Nils Aall Barricelli who pioneered cellular automata 15 years before John Conway, artificial life 20 years before Christopher Langton and chaos theory 15 years before Benoit Mandelbrot. Barricelli called his creation "symbioorganisms", but it's interesting to try to demystify them without any analogies with living organisms.

The playing field is a finite, circular 1D space of discrete squares. Squares can be occupied by one of many different kinds of elements. Each kind of element has a propensity to move through the space with a constant step. To this space of elements striding around, Barricelli adds 3 rules. (Well, he experimented with many different tweaks in his papers, but this is one concrete, elegant formulation.)

Just adding the first 2 rules gives rise to some very interesting behavior. Here's a pretty picture:

Save a copy for yourself. You'll need to edit the html to tailor the table dimensions for a specific context.

Saving the table downloads a new copy. (You'll probably want to rename it to the original; that bit is kinda janky.)

As I said before, just view source on this beauty! 😍

The problem: implementing text editor operations as lines might wrap or scroll.

e.g. clicking with the mouse to reposition the cursor, or pressing the down arrow (which might cause a scroll)

The key new solution: an API of primitives that make such operations fairly self-evident to build.

to_loc: (x, y) -> locto_coord: loc -> x, ydown: loc, dy -> locup: loc, dy -> loc

Find the location at the start of a screen line dy pixels up from loc.hor: loc, x -> locI think they might be applicable to any pixel-based editors that use proportional fonts. They seem independent of the data structure used by the editor. I use an array of lines, and so locations are defined as (line_index, pos) tuples, where pos counts in utf-8 code-points.

There's probably a few bugs but hopefully it'll stabilize quickly. I'd appreciate people trying it out.

Lessons from this experience:

I think I now better understand the "abyss".

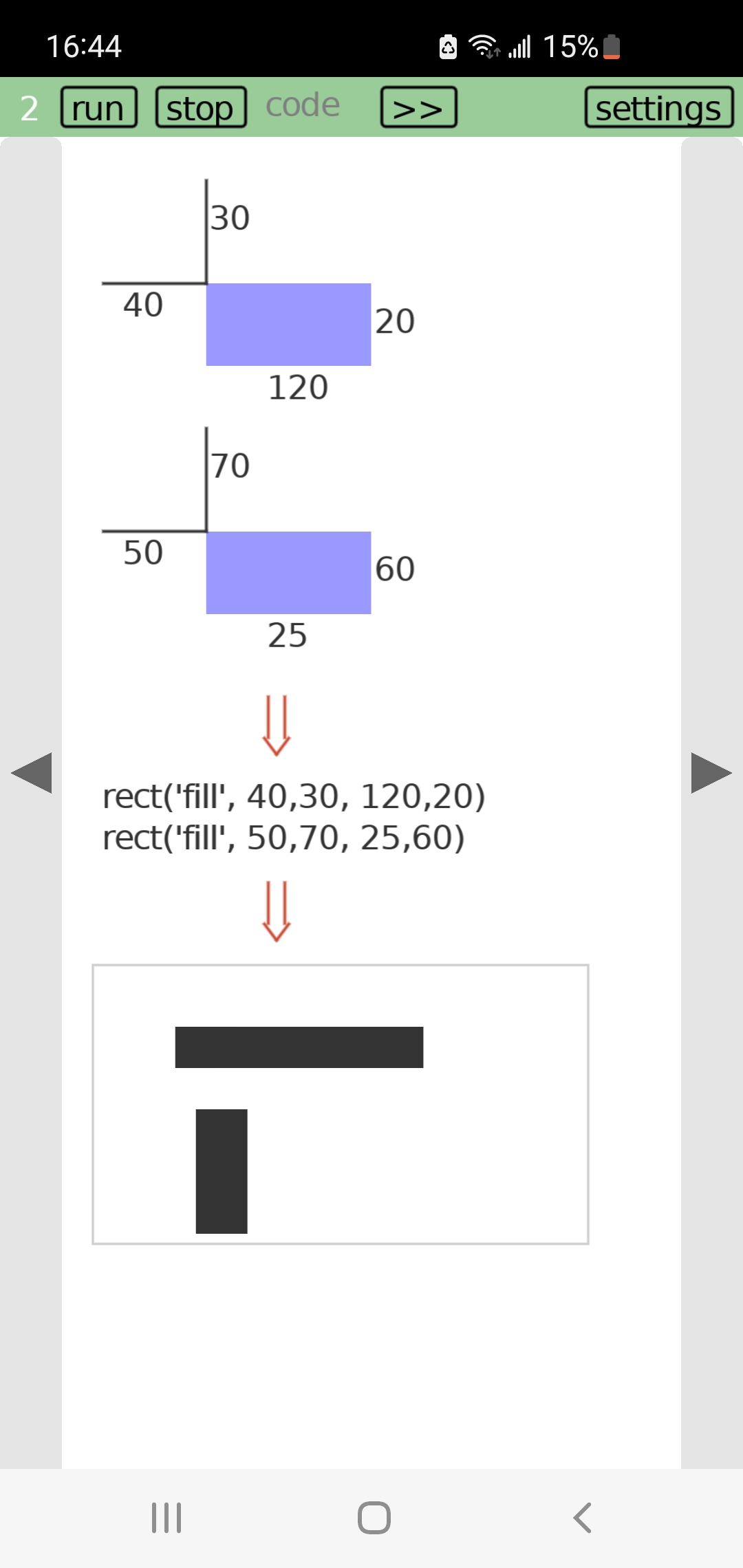

The code in the screenshot is a function to convert a mouse click (mx, my) into the location (line_index, pos) of the character at that point on the screen.

The problem is much of this function is boilerplate shared with several other places, such as the code to draw text on screen, compute the height of a wrapped line, etc. The boilerplate makes it difficult to see the business logic unique to this particular function, and so creates pressure to prematurely create an abstraction to "DRY things out". Highlighting the shape of the boilerplate in pink helps the eye to focus on the unique business logic in the protrusions, and so counters the pressure to hide the boilerplate before I've figured out the best way to do so.

(As an aside, this is an example of what I think of as "programmer-configured highlighting". We've gotten used to our editors deciding what to highlight for us, and we just pick the colors. One little tool I use everyday is the ability to highlight specific identifiers which flips this around: I pick a word, and the editor picks a color at random to highlight it with. And the highlight persists across sessions. The color of the State variable in the screenshot was selected in this manner.)

Until now I've been developing the editor the "usual" way, which for me consists of needing some computation, figuring out the most convenient place to perform the computation, then squirreling away the result somewhere it's available when needed. In an effort to get myself out of the rut of the inevitable problems of indirection and cache invalidation that result, I've been trying to replace all my ad hoc data structures with on-demand computation based on the base state of the program. And what I've been ending up with is umpteen variations of this pictured algorithm, just with different code stuck on to the protrusions.

There may be an abstraction that comes out of all this, but I don't see it yet. And as CA says, a flower isn't made up of identical petals. Each one evolves uniquely as a part of the whole.

Here's the Lua code skeleton corresponding to that drawing. The ellipses correspond to protrusions in the drawing:

for line_index, line in array.each(State.lines, State.screen_top.line) do

if line.mode == 'text' then

local initpos = 1

if line_index == State.screen_top.line then

-- top screen line

initpos = State.screen_top.pos

end

for pos, char in utf8chars(line.data, initpos) do

if char:match('%s') then

if line_wrap_at_word_boundary(State) then

...

else

...

end

else

if x+w > State.right then

...

else

...

end

end

end

else -- drawing

...

end

end

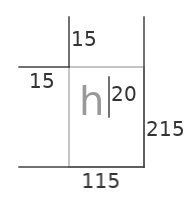

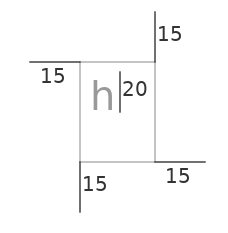

…might represent a function for initializing a text editor widget with the following signature:

edit.initialize(top, left, right, bottom, font_size)

And the numbers indicate a specific call to this function:

edit.initialize(15, 15, 115, 215, 20)

Interestingly, these alternative semantics would make for a more pleasing glyph.

edit.initialize(margin-top, margin-left, margin-right, margin-bottom, font-size)

(Just a mockup to convey the idea. Plan is just to use this notation with pen and paper.)

Is this picture intelligible without any explanation?